Theresa Snow & Salvation Farms: Bringing Food Security to Vermont

If farms are an autobiography, then Salvation Farms tells the powerful story of Theresa Snow.

Salvation Farms owns no land or tractors. You won’t find a big red barn, gardens or chickens. But thanks to Theresa Snow’s broad vision and tireless efforts, it has food. And plenty of it.

Snow started working at Pete’s Greens in Craftsbury as she wrapped up her final semester at Sterling College. After serving as an AmeriCorps volunteer in New York City immediately after 9/11, Snow returned to Pete’s for another three years. During that time she honed her vision for what would become her life’s mission: keeping farm-raised food from going to waste and feeding people.

Some sobering national statistics: 40% of all food produced in the U.S. never reaches people. 20% of edible-quality food never leaves the farms, and 30% of food from retail and prepared meal sites gets wasted. Here in Vermont, 84,000 of our residents are food insecure, meaning they lack reliable access to a sufficient quantity of affordable, nutritious food. The state also imports millions of dollars of food for the 19 million meals served annually in nursing homes, prisons and schools. Statistics like these gnaw at and motivate Snow.

“Sterling College taught me to be a responsible steward of the natural environment,” says Snow, executive director of Salvation Farms. That ethos remains fundamental to Salvation Farms, which Snow co-founded in 2004. Snow was troubled by the amount of quality unused product she saw on farms, through no fault of the farmers. In the summer of 2004, Snow gathered a group of students from Sterling College to glean the surplus produce from Pete’s Greens fields and distribute that product to preschools, elder care centers and food shelves around Craftsbury and the Lamoille Valley. Other farms in the valley got on board and welcomed those initial gleaning initiatives. In the process, Snow forged relationships with NOFA-VT and the Vermont Foodbank. “If it weren’t for those farmers and organizations believing in my vision,” she says, “Salvation Farms never would have come to fruition.”

Photo 1: Theresa Snow partaking in Pick for Your Neighbor, an orchard initiative she established.

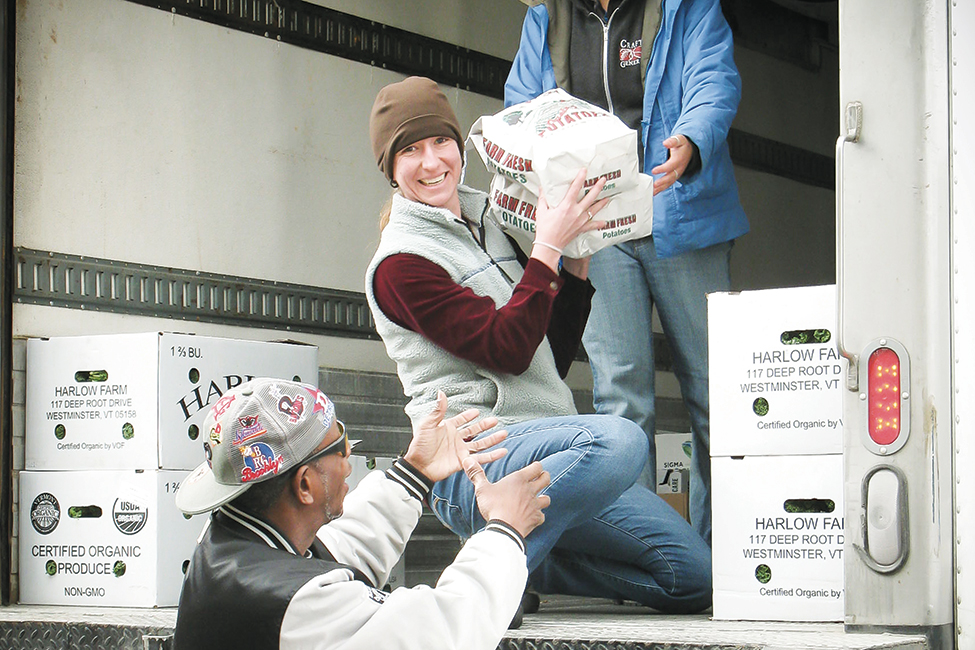

Photo 2: Snow, center, unloading a truck of produce gleaned from a Vermont farm.

Photos courtesy of Salvation Farms

Snow grew within peddling distance of her grandparents’ dairy farm in Morrisville, her home surrounded by backyard gardens, cows and pigs. Aside from her time with AmeriCorps, she has remained entirely dedicated to developing innovative programs to address food waste and food independence in Vermont. On a personal note, I ventured out on many gleanings with Snow in 2010. Her energy and humor buoyed me as we gathered cabbages, leeks and winter squash. I’ve heard her present at numerous conferences since then and marvel at her passion and courage. Theresa Snow is one of the most grounded, determined and selfless individuals I’ve ever met. Truth be told, she remains one of the people who inspired me to shift my career from teaching to farming and writing. She has that impact.

Since its inception, Salvation Farms has worked to reclaim surplus food and redistribute it through the proper channels to feed the vulnerable residents of Vermont. Equally important are educational outreach and community engagement. Snow believes that communities should be less vulnerable and more food independent: to have access to land, sow seeds and get that food onto people’s plates. While working with the Vermont Foodbank, Snow established their gleaning program and Pick for Your Neighbor orchard initiative. “Ideally we can develop community-based pods that are successfully capturing food and feeding their own communities. That’s food security.”

Professor Nicole Civita, assistant director of the Rian Fried Center for Sustainable Agriculture & Food Systems at Sterling College, is working closely with Snow this spring and offers this reflection. “Many Americans have become accustomed to living in an environment of relative plenty; this can make us careless about our resources and our relationships. It leads us to forget about all the hands that touch our food before it reaches our plates. It leads us to forget that we are stronger when we work together than when we work alone. Salvation Farms works not only to rescue surplus food but also to stop our slide down this slippery slope and start down a path paved with gratitude, respect and appreciation.”

A systems thinker, Snow believes that Salvation Farms can facilitate these conversations about food independence and orchestrate resources. “We strive to help community-based organizations build localized food networks. That may mean fostering a creative workforce development connection with the Department of Corrections or New Americans, or collaborate with the Vermont Youth Conservation Corps to get more food out of farm fields, or engage with Black River Produce and Vermont Foodbank as haulers and distributors.”

“Our mission is to build increased resilience in Vermont’s food system through agricultural surplus management. We are driven by three primary goals: to reduce food loss on farms, to increase the use of locally grown foods and to foster appreciation for Vermont’s agricultural heritage and future.”

Elana K. Dean, a researcher from Isgood Community Research, is working with Snow on a study to assess the amount of food loss in Vermont. Research includes input from farmers on their preferences for managing excess produce, and these findings will help design programs to address food waste. Dean observes that “Theresa is entirely dedicated to creating a sustainable food system in Vermont. She values collaboration highly and creates spaces to work with and learn from farmers, nonprofits, professors and others. She works around the clock on Salvation Farms.”

Salvation Farms oversees the Vermont Gleaning Collective, a statewide association of six, soon to be seven, autonomous gleaning initiatives. Gleaners are volunteers, led by trained coordinators, invited onto a farm to harvest or capture quality food that won’t go to market. In 2015, the Gleaning Collective had 750+ volunteers who dedicated 2,580 hours of service to 90 farms across Vermont and captured 220,000 pounds from waste, distributing that product to more than 200 sites.

The Gleaning Collective helps farms serve their communities by ensuring that the crops are captured and distributed while the product remains fresh and viable. “Gleaning is the gateway activity that leads to this surplus management system. To be effective, we have developed efficient systems that get the food from the fields to the people as swiftly and as safely as possible.”

Salvation Farms gained federal nonprofit status in 2012 and still collaborates with the Vermont Foodbank as a primary partner. “If we can continue to streamline the process,” says Snow, “it’s a cost savings. Working together, we can fill a need.”

For example, farms occasionally have an abundance of product that exceeds local need. Typical crops include apples, potatoes, green beans, peppers and winter squash. That situation led Salvation Farms to develop the Vermont Commodity Program. Gleaned crops are aggregated, cleaned, quality-assessed and packaged into smaller portions for distribution through charitable or institutional food sites.

The challenges can seem daunting. “I sometimes ask myself, ‘Why do I get up at 4am? Why can’t someone else pick this up and run with it?’ I think my drive came from recognizing the incredible injustice of agribusinesses and my desire to undermine corporate control of our food supply. Food is a powerful tool for social change as well as for oppression and exploitation. I remember feeling so helpless when I worked as an AmeriCorps volunteer in Manhattan during 9/11. I wanted so badly to help these devastated people who had nowhere to turn and who had exhausted all their resources. My work with Salvation Farms allows me to help my neighbors and alleviate in some way their burden through providing more access to food.”

What can we do to support Salvation Farms? “Money is the obvious answer,” Snow says. “Funding is increasingly crucial as our programs and team build momentum. We also encourage people to seek out their regional gleaning group and get involved that way. Approach your legislators and tell them why rescuing and redirecting food to your neighbors is vital for your community and for our future. All these steps make a difference.”

Salvation Farms is now leasing a space in Winooski that will house a workforce development program, doing similar work to what inmates accomplished with commodity crops delivered to the Southeast State Correctional Facility in Windsor. The New American population in the Burlington/Winooski area may be a potential source of workers. Snow envisions equipping the workforce with practical skills and education along with performing purposeful work. The facility has a loading dock, cold storage, space for a wash-and-pack line and potential for minimal processing of product. She envisions, to start, two four-month cycles, from September to December and then January to April. “Our base expectation is running 75,000 to 100,000 pounds of food through this facility in each of the cycles.”

Theresa Snow has spent her career forging enduring relationships with people across Vermont and beyond. Her innovative programs now serve as models for other states. How does she sustain this pace and maintain her health? Snow admits sheepishly, “I have a hard time quieting my mind at night but I do sleep. And that tells me I’m doing the work I am supposed to be doing.”

Maria Buteux Reade works at Someday Farm in East Dorset, and whenever she feels her energy or optimism flag, she often channels Theresa Snow, the exemplar of grit and grace.